Trying to give everyone equal opportunity to do what they want to do in life requires economic fairness. And one of the ways to develop that is to have a reliable water supply to enable industry and people to thrive.

Geraint Burrows, Founder and CEO, Groundwater Relief

Today is Protect your Groundwater Day – a day created by the National Ground Water Association to ‘provide an opportunity for people to learn about the importance of groundwater and how the resource impacts lives.’

In recognition, we wanted to share a story about the use of our Leapfrog software to support work done on a South Sudan project. We learned about this work from Geraint Burrows, founder and CEO of the non-profit Groundwater Relief (formerly known as Hydrogeologists Without Borders UK).

Groundwater Relief focuses on providing groundwater expertise and support to organisations working on water related projects within the humanitarian and development sector (often referred to as WaSH projects – water, sanitation and hygiene). The charity has a membership of over 230 groundwater experts and specializes in linking the right people to a particular problem on short notice. This quick turnaround is vital due to the tight timelines that NGOs operate within.

“For a charity to recruit a staff member to implement a one-year project, it might take them two or three months to get the right person,” Geraint said. “That only leaves nine months to actually implement the project.”

Geraint knows how important it is to have the right person on a project, as he’s also a WaSH engineer who has spent extensive time in the humanitarian aid sector. He’s worked with Oxfam, Medecins Sans Frontieres and the International Rescue Committee – which meant he was well-experienced by the time he founded Groundwater Relief.

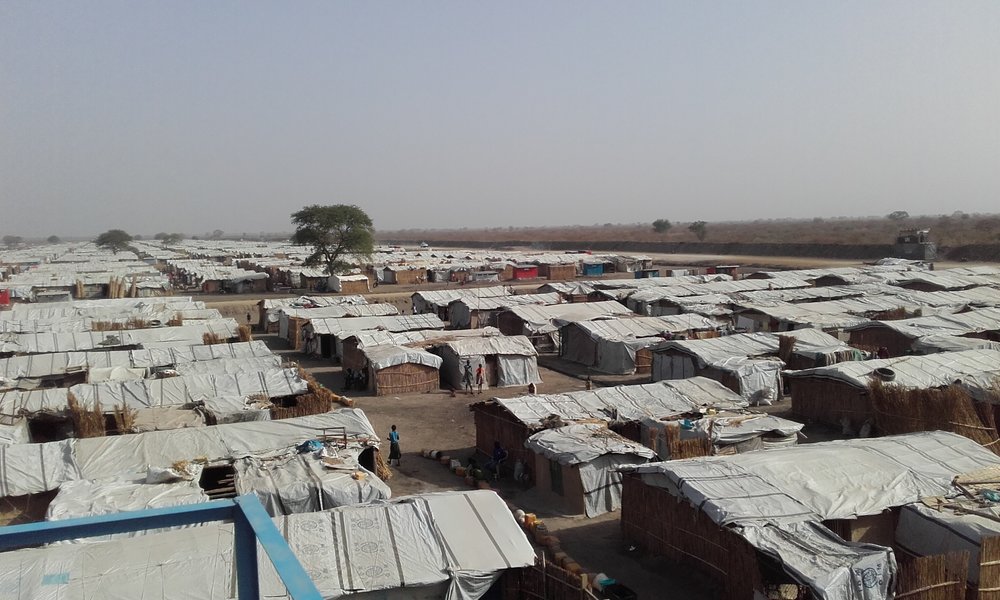

Geraint’s organisation has worked on multiple projects, including one at the Bentiu Protection of Civilian’s (POC) camp in South Sudan. In March 2016, Groundwater Relief was commissioned to assess groundwater conditions at the Bentiu camp, which at the time, had a population of 125,000 people. It’s the largest of six sites established by the United Nations Mission in South Sudan to provide some reprieve for citizens affected by the ongoing civil war.

His team was called in to determine what the groundwater potential was below the camp, as they knew there were water resources available, but some of the water wells weren’t producing much water.

“Wells had been drilled throughout the camp, but some of those wells were suffering from sedimentation issues or they were not very productive,” he said. “Organisations were considering other water supply options for the camp, which would have been potentially more high risk and expensive than drilling another borehole in the camp.”

It was an urgent situation, as those in the camp were on very minimal amounts of water. Individuals only had access to nine litres of water per day. (To put that in perspective, the average New Zealander uses over 200 litres per day.)

“The needs were very stark,” Geraint said. “Nine litres per day is well below set emergency standards of 15 litres of water per person, per day.“

Geraint’s team began characterising the water resources below the camp by first pump-testing the existing wells and sampling for water quality. They also obtained the drill logs for the wells and used that data to create a 3D model in Leapfrog, which gave them further insights into the aquifer.

“The model gave an indication that there might be two aquifer units separated by a thickness of clay, within the immediate aquifer underlying the camp,” Geraint said.

Accurately characterising the aquifer was important, because if the team could understand the subsurface, they could also understand how to best harness the resources there. But that wasn’t the only benefit they saw from 3D modelling.

“3D modelling proved a very valuable tool, not just for identifying those two aquifer units, but for outlining that message to a non-technical audience,” Geraint said. “When individuals could see the model in a 3D sense, they could suddenly understand more about the actual resources, which otherwise would have been difficult for them to conceptualise in their heads.”

This included the decision makers who managed funds and made the decisions regarding water supply for the Bentiu camp. Based on the communicated aquifer results, decisions were made to forgo the more costly water supply options, such as water trucking, and invest in further water well drilling.

Since the program ended, three new water wells have been drilled. For Geraint, this was one of the most important outcomes of the program.

“Later on one of the old wells, a key well for the camp, failed,” he shared. “If it hadn’t been for those new wells being installed, that would have caused a really big problem for the camp. So I think the community was saved from some considerable suffering as a result.”

You can learn more about the Bentiu POC project from the case study on the Groundwater Relief website.

—————

Groundwater Relief is an organisation supported by a membership of over 230 hydrogeologists and groundwater professionals. Their members work within water utilities, mineral extraction companies, environmental consultancies, oil and gas companies, government and educational institutions from across the globe.

Their members join to utilise and volunteer their skills and knowledge to support the sustainable development of groundwater resources for the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people.