When the Aqua Survey team headed into the mountains of southern Laos, it knew the challenges that lay ahead. The company’s task: to pit its technical expertise and specialized detection equipment against what is commonly described as the most difficult UXO clearance area in the world.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail, a network of roads linking North and South Vietnam, stretches some 3,000 km across Laos and Cambodia. American forces seeking to cut off North Vietnamese supply lines during the Vietnam War bombed the trail heavily, dropping more than 3 million tons of ordnance on Laos alone, with many failing to detonate. Hidden under dense foliage and buried underground, these UXOs continue to maim and kill Lao civilians today.

UXOs also pose an economic hazard: larger bombs can remain dormant for years until a heavy vehicle such as a bulldozer rolls over one. This ongoing threat means infrastructure projects such as roads and schools require costly bomb-clearing operations.

The first task of Aqua Survey, a Kingwood, New Jersey-based environmental survey company, was to survey a 1-mile stretch of dirt road. That might sound like an easy job to a lay person, but the region’s unique challenges have foiled any number of previous attempts to clear it of old bombs. The challenge lies in the country’s very soil, which is rich in aluminum and other metals,

“The soils were so conductive that a 250-lb. bomb would disappear in the background EM response at 1.2 metres,” says Aqua Survey President Ken Hayes. “This compares with a detection range of 4 metres in the air.”

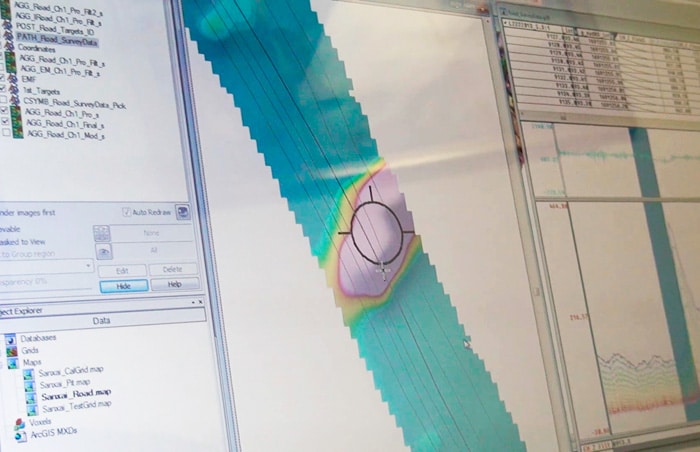

The Aqua Survey team used an EM63 time-domain electromagnetic detector to record multiple-time gates which showed subtle changes in background conductivity. The readings were then processed through a proprietary utility, and the output was seamlessly imported into Geosoft UX-Detect for gridding, mapping and spatial refinement of target locations.

The scale of the country’s UXO problem quickly became apparent: in the single mile of road Aqua Survey examined, scans located more than 700 dense metallic targets.

Hayes points to yet another challenge the team faced: many of the detected objects were not bombs but rather pieces of metallic debris strewn along the road. The next step was to identify the signatures most likely to be UXOs.

Using a combination of techniques, we generated a prioritized target list that isolated larger and higher conductance targets more likely to be munitions of concern,

The final result, a list of 29 items most likely to be large, buried, bombs, was handed off to specialist teams tasked with UXO disposal.

The team’s second project was at the Sepong gold-copper mine, also in southern Laos, where large bombs are found on a regular basis. Sepong posed a special sort of challenge in that the mine boasts some of the most conductive soil in the world. Strict safety procedures mean the mine has never had a bomb-related injury, though it paid the price in excavation time. Speeding up UXO identification would mean massive cost savings – a vital concern in a country where mining accounts for more than 10% of the economy. Here, too, Aqua Survey’s expertise lived up to the challenge. Reconfiguring the equipment and adapting the software allowed the team to distinguish between responses from the ground and the bombs.

In a land where the ground itself holds both great promise and mortal danger, the dormant threat may have finally met its match.