Nigel Halsall, Solutions Consultant, trained and supported personnel from subsea services provider N-Sea. So when the manager there asked if he’d be interested in spending three weeks participating in a marine UXO survey his immediate response was, “of course I would.”

It wasn’t as simple as stepping aboard. Preparation meant taking a fitness certification exam, and completing a four-day BOSIET (Basic Offshore Safety Induction & Emergency Training) course. “We were required to have this survival training,” says Halsall of the course he attended at Norwich. “It included things like hazardous escape chutes and escape from a helicopter underwater.”

The course, by professional safety training firm Petans, was comprehensive and also covered the offshore industry, personal survival, survival craft and life raft drills, post-escape first aid, firefighting, compressed air emergency breathing systems (CA-EBS), and lifejacket pocket plus emergency breathing systems (LAP-EBS).

Halsall explains LAP-EBS. “You fill the vest with one breath of air and then re-breathe it for about 30 seconds.” He says they are particularly necessary if you’re plunged into freezing cold water. “You can’t hold your breath … the shock of the cold water means you can’t hold your breath for very long.”

The N-Sea invitation was to participate in a survey for a proposed natural gas pipeline through the Baltic Sea. For the subsea services, N-Sea was contracted to undertake munitions screening surveys at a number of sites along the route. The objective was to detect all munitions objects on the seabed or in shallow burial that might pose a risk to installation and operation of the pipelines.

Halsall was on board the survey vessel for the offshore Finland segment of the route. It was N-Sea’s newly-chartered SIEM Barracuda 5,000-tonne offshore support and survey vessel, which was accompanied by an ROV with magnetometers. “It’s like a massive floating hotel, really nice,” he says. “We had our own cabins, a gym, and good food.”

His role was with the survey part of the operation; identifying targets for the explosive experts who were on board the vessel following behind. The EOD experts would look at each target and make an assessment.

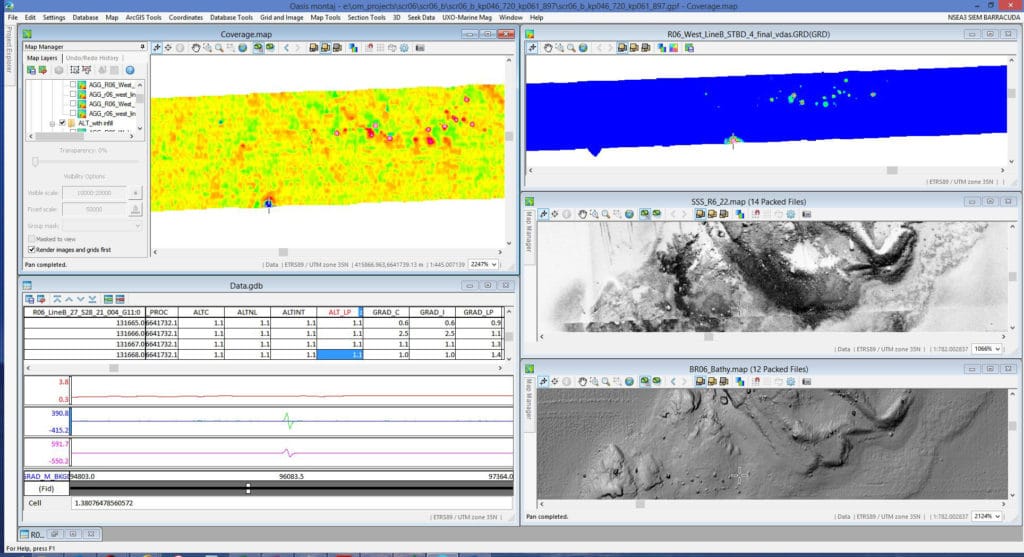

Halsall worked the night shift, 6 PM to 6 AM. “With my Oasis montaj background I was mainly responsible for overseeing the targets picked, calculating target parameters and creating target lists,” he says. For this part of the survey, positional and magnetic data were collected: XYZ and nanoteslas. Bathymetry data had been collected in a previous survey. They also had a live feed from cameras attached to the ROV magnetometer frame, which sometimes would reveal an image of an actual bomb.

It was an impressive team effort. “For large offshore jobs, there are lots of geophysicists, four or five of us, with offline and online surveyors for navigation,” explains Halsall. “We were in the offline room and next to us was the online room. The ROV pilots use the online data which is more critical work because it’s all live. The data were sent back to our room.” The ROV pilots plotted out their route based on coordinates provided by the ship’s crew and the surveyors, along with the client’s plans.

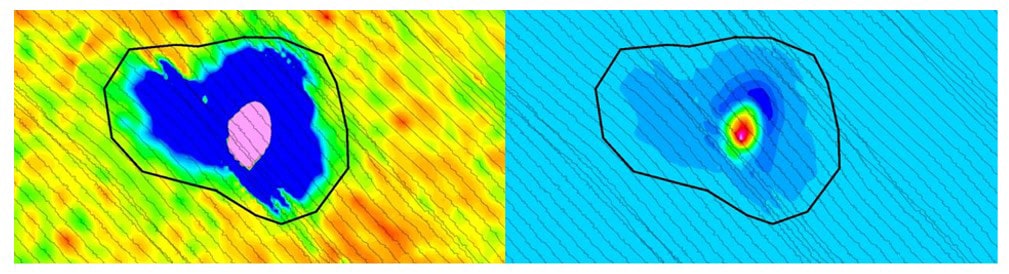

How were suspected UXO targets identified? “Usually we agree parameters with the client before the survey starts,” explains Halsall. “They’ll do a test where they throw ferrous objects over the side and survey over them to test the equipment and define the appropriate target parameters. We put those parameters in the software. So on the grids we pick those anomalies – we’ll pick out targets that have those high values.”

He says Oasis montaj was the primary software used onboard for creating most of the final deliverables. The UXO Marine extension was used along with custom made scripts to carry out specific QAQC steps, followed by additional magnetic data corrections, e.g. for magnetometer noise. “The process created analytical signal grids for picking of targets using the Blakely grid based picking method,” says Halsall. “There are criteria to follow, like if it’s a particular area anomaly or amplitude, if it’s a seabed feature they label it for interpretations.” That information goes off to an EOD or explosives expert for further analysis during the target investigation.

Concentration of targets varied widely. Highest are near the shore where they could number in the thousands. But further offshore there might only be ten. Much research is done prior to the survey. “From mapped areas they can identify wartime mined areas where they know there were lots of mines and dumping grounds,” says Halsall. “They tend to avoid these but there are some they don’t know about so there is always a risk.”

“There is often a lot of scrap metal. But you can’t really make any assumptions until they’re investigated; even if it’s only a small anomaly. It still might be a large bomb that has perhaps lost its magnetic casing.”

He says the volume of data not only collected, but created as deliverables from the raw data to send to the end client was eye-opening. “I was impressed with the way N-Sea created scripts in Oasis montaj to ensure data consistency,” he says. “Since my job at Geosoft involves a lot of data management it was also surprising to see how large amounts of data were managed offshore.”

It was a great learning experience. Having trained Geosoft marine survey clients for more than eight years, Halsall found the experience of interacting with the different offshore and onshore teams most useful. “Often while at Geosoft I like to focus on the more advanced features such as modelling targets,” he says. “However while offshore I was able to see how important the more basic functionality is and the need to clearly explain different techniques and tools to a broad range of people with different backgrounds, especially quantifying any sources of uncertainty.”