War has always come with a heavy cost, all too often borne not just by those who lived through the conflict but by people who were not even born until long after its end. As the explosive remnants linger for decades, so do their debilitating effects.

Over the decades, groups large and small have focused their efforts on cleaning up unexploded ordnance (UXO) and other explosive remnants of war (ERW). Most tackle the problem in the most direct way: Surveying for UXO, digging them out of the ground, and safely destroying them. But there is another side to the work: Coming up with new, more effective ways of addressing the problem. For the past 17 years, this has been the stated goal of the Golden West Humanitarian Foundation, a small group of highly trained specialists focused on UXO-related research and development.

Chief of Detection Dr. Marcel Durocher and Detection Operations Officer Mr. Heang Sambo have been working with Golden West on detection and survey tasks for over 10 years.

East DRED lanes at the Golden West test center in Kampong Chhnang, Cambodia; green dots are where the Free From Detonator (FFD) landmines and UXO are buried and the yellow dots are scrap metal signatures.

Supporting role

The foundation’s team does engage in clearance work if a fellow organization comes across an unusual challenge or requires specialized assistance, however, Roger Hess, Director of Field Operations at Golden West, emphasizes that their primary role is enabling other groups’ clearance operations.

“You have very large organizations like Norwegian People’s Aid, Mines Advisory Group, Halo Trust, etc., all doing fantastic things in clearance, and they employ thousands and thousands of people,” he says.

Rather than competing with these groups for limited donor and government funding, Golden West created a small, specialized group that helps everybody, and is focused on innovating to find field supportable solutions that work in developing, post-war countries.

Verifiable results

The first step in UXO clearance is finding the buried remnants, and the process is far from straightforward: Terrain conditions affect detector sensitivity and it takes a lot of practice to filter out as many inert objects as possible, while still ensuring no UXO are left behind.

Golden West’s Detection Technology Manager Marcel Durocher points out that the configuration of detectors isn’t always correct for the particular environment – but all too often device manufacturers simplify device operation by hiding the underlying assumptions from the user.

“The user just punches in the numbers and a pretty picture comes up. There’s no understanding of what was involved in the processing. Sometimes it works out fine, but in other cases the assumptions are not valid for that particular environment and the results are not good.”

Durocher, who introduced Geosoft’s Oasis montaj and UXO software to Golden West when he joined the organization in 2006, says the latter offers much greater flexibility and allows users to calibrate the detectors to the circumstances.

“Oasis montaj provides more options on how to process the data and access to more predefined filters. You can also input user-defined filters if you choose, which isn’t possible in other software packages. It’s more mature than anything else on the market,” he says.

Ensuring survey results are consistent and verifiable is essential. “You’re never remembered for what you’ve found; you’ll always be remembered for what you’d missed,” Durocher says.

The Golden West approach to surveys relies not only on operator expertise but also on a wealth of data produced by its Detection Research, Evaluation, and Development (DRED) facility – the only one of its kind in South-East Asia. At DRED, six lanes of different soil serve as a testing ground for detectors: Everything from clean sand to metal-rich laterite, and concealing devices ranging from antipersonnel mines 10 cm deep to 750 lb. bombs 400 cm deep.

“All landmines and most UXO still contain the original high explosive main charge, however the primary explosive has been removed from the detonator in the fuse assembly. There are no surrogates or simulated items; if something was missed by the detector then an actual landmine or UXO was missed,” says Hess, explaining that some items have come from stockpiles while others were recovered from actual clearance operations and made safe by the Golden West team.

“The only difference between the DRED site and an actual clearance task is that the items will not explode in the DRED lanes; we refer to it as a ‘Zero Excuse’ approach,” he concludes.

Durocher and his team have used the lanes to painstakingly test various detector configurations. One of the tools they use is a purpose-built, 4m-high PVC tower and a huge array of different targets.

“They will raise or lower the array with a target underneath it, log where it starts to pick it up, where it maxes out, then raise it back up and move it about 10cm and start the whole process again,” says Hess.

Mapping the effectiveness of various sensor configurations involves hundreds of measurements. The result is a database that can be processed in Oasis montaj to produce 3D models of UXO responses for a wide range of munitions.

Once in the field, Golden West operators bury inert munitions of the type most likely to be found at the site. Each day, the operators must show that their equipment can consistently detect these reference targets.

Tests using the UPEX 740 detector – a very widely used device – has yielded another accomplishment: two configurations (a 2.4m octagonal and a 2x2m “Open Loop”) outperformed the manufacturer-recommended configurations. Golden West took the results to Ebinger, the device’s manufacturer, who then incorporated them into the product. Golden West also shared the results with other NGOs in the region, allowing them to boost sensitivity by up to 25% with a $10 investment in some PVC pipe.

Professional data-logging has been used in commercial survey tasks for over two decades in Europe and North America, however it’s only recently been accepted into the Humanitarian Mine Action (HMA) scope.

“Marcel and I have proven many times that a few days of work by a small detection team that knows how to correctly use data-logging methods will keep a 12-man clearance team busy for a month, easily,” says Hess.

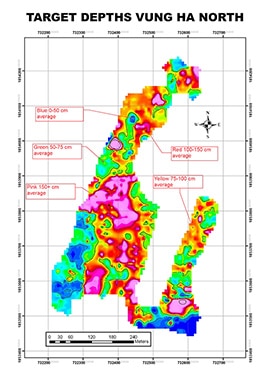

Most of that time, however, will be spent digging up inert pieces of metal – Hess says that with modern technology, he still expects to see a 95% false positive rate. He offers the example of Vung Ha, a 27-hectare site in Vietnam. After the initial survey located over 26,000 potential targets, Durocher re-configured the detector loop; the second pass identified just 4,200 likely targets. Of those, just 507 were found to be actual UXO, fewer than 2% of the initial count. This result highlights another advantage to data-logging: The precise GPS-based identification of target positions meant only 10% of the total area had to be manually cleared, as compared to using mag-and-flag methods.

Durocher notes that the Geosoft software greatly simplified the re-configuring process for the project.

“When you change the size of the loop, you have to change your target thresholds, and you can do that very easily in Geosoft. You can process the data, look at it, and if you’re not happy, change the thresholds again, go back and process it, and you can do that in just a few minutes,” he explains.

Challenging conditions

When tips from local residents set Golden West on the trail of ammunition barges that were reportedly sunk in the Mekong and Tonlé Sap rivers, finding the wrecks was just part of the challenge. Hess describes the recovery as “brown water” work with good reason: The water is so murky that visibility drops to zero – “we train people by painting over their masks,” says Hess – leaving divers completely dependent on their sense of touch. To make matters worse, the current keeps everything moving and the crews are constantly at risk from weeds, logs, or loose fishing nets – none of which they can see coming.

The underwater environment makes accurate survey data all the more vital: Qualified divers are in short supply and their time is best occupied with recovering actual UXO, rather than inert chunks of scrap.

Hess also points out that brown water surveys have a limited shelf life. “The next flood, high tide or storm may bring obstructions that were not there before; your window of opportunity to work is limited.”

Yet the challenges of the brown water environment can yield spectacular results. According to Durocher, the very first search Golden West conducted on the Mekong located a sunken ammunition barge, from which divers recovered over 11 tonnes of ammunition.

Under the sea

Buoyed by the success of the brown water survey work – which the foundation developed with no external funding – Golden West has now taken on an even greater challenge: Surveying the coastal waters of the Solomon Islands, where villagers have been living under UXO threat since the end of World War II.

The age of the munitions is in itself a cause for concern, explains Durocher. As salt water degrades their integrity, explosives – some of which are highly toxic – seep into the sea and poison the marine life and coral reefs.

The project will focus specifically on shallow waters, says Durocher, because people in the region have also been known to use found UXO for fishing – what Durocher and Hess call “fish bombers.” At best, this method indiscriminately kills all sea life in a large area. At worst, Hess says, people mishandle unstable devices and “families get wiped out.”

But marine surveys offer a whole new set of challenges, starting with the conductivity of salt water.

“In fresh water, we can use magnetics, electromagnetics, and sonar. But because salt water is conductive, electromagnetics are of limited usefulness,” Durocher explains.

Ebinger, makers of the UPEX 740, have come up with an idea that may render pulse induction devices usable in salt water; testing the new device in the field is one of Golden West’s goals for the project, says Hess, adding that a wide range of sensors and software packages are to be put through their paces. So little clearance work has focused on coastal seawater areas that we simply don’t know what will work and the pitfalls may be.

“We can make our best guesses based on performance in other situations, but will it actually work, will we be able to accurately get the signals, log the signals, properly record where they were so we can find them again, that’s the crucial question.”

Golden West will be using Geosoft Oasis montaj, and its UXO Marine software, as the baseline against which they will judge the results.

The Solomon Islands project is still in its early stages, but it comes at a time of growing attention to similarly affected shallow coastal waters. As clearance activity in these challenging conditions increases, so will the importance of having the real-world performance data being gathered by Golden West.

Explosive Harvesting System

One reason the Golden West name is so well known in South-East Asia is what may be one the group’s biggest success to date: The Explosive Harvesting System (EHS).

Roger Hess, Golden West’s Director of Field Operations, says he first came up with the concept while serving with the Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) teams in the US Army.

“We had a support project in Rwanda with a $2.4M budget and spent $800,000 of it getting explosives there. That’s when I came up with the idea of recycling the explosives which are already in-country,” he says.

The need became all the more poignant after the September 11 attacks.

“The US government was putting about $500,000 every year into supplying explosive charges to Cambodia. After 9/11 that dried up because of security concerns, and in 2001-2002, almost all of the clearance operations in Cambodia were shut down because no one wanted to provide them with explosives to destroy the mines,” explains Hess.

When Hess joined Golden West in 2004, he brought the concept of EHS to Golden West founder Joe Trocino, a chemist by training who had previously developed a low-cost binary explosive for UXO disposal. The EHS offered an elegant solution: Recover the main charge explosives from large capacity munitions and use it to make small disposal charges. In other words, use UXO to destroy UXO.

Previously, Cambodian clearance teams were buying commercial explosive booster charges designed for the mining and quarrying industry, paying up to $5 for each 200-300g charge. But because the operators weren’t trained in proper application and the charges were not designed for this task, they would simply pile on more explosives to destroy the munition.

“They would maybe spend $30-$40 on a single shot, just to get rid of a projectile or a bomb,” Hess says.

According to Hess, Golden West designed smaller charges that direct maximum force into the target. Each 100g charge must fully penetrate an 8mm mild steel plate; Golden West perform random QC testing during production to make sure this standard is met or exceeded.

“If you know where to apply it to a munition, a single 100 gram charge can destroy a 500lb bomb, where people would previously use 2kg of explosives,” he says.

The 7-person EHS operation produces over 3,000 charges per month, which are supplied to Cambodia’s fully licensed and accredited NGOs free of charge. To date the facility has produced over 380,000 charges, and is currently supplying all of the explosives used by local and international NGOs conducting humanitarian landmine and UXO clearance Cambodia.